The recent and tragic deaths of young black men at the hands of police in Ferguson, Missouri, Staten Island, New York, and suburban Dayton, Ohio have forced a national conversation about the relationship between policing and race in the United States. This month historian Michael Flamm roots our current debate over police violence, racial discrimination and mass incarceration in the “War on Crime” declared by President Lyndon Johnson fifty years ago this year.

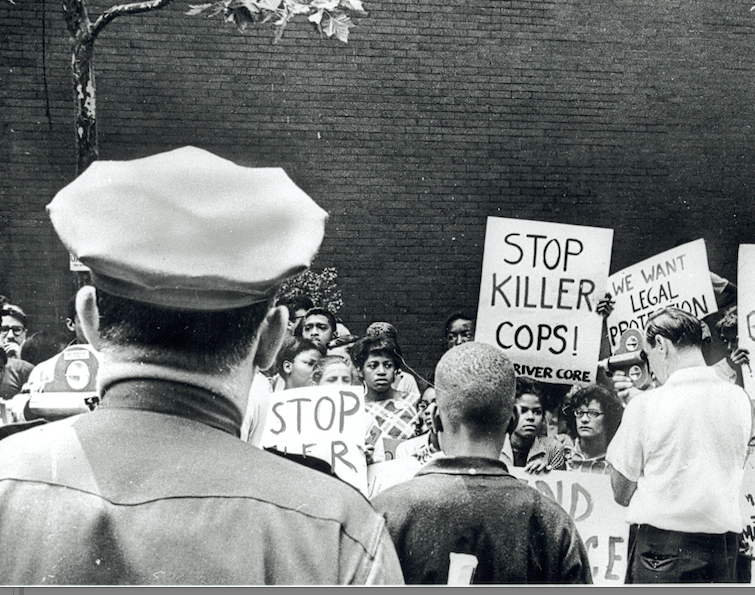

“Hands up, don’t shoot!”

Demonstrators chanted these words at police in the aftermath of the shooting of Michael Brown, an unarmed black teenager, in Ferguson, Missouri in August 2014. The incident ignited weeks of protests and riots.

It also led to a nation-wide debate about how white officers patrol black neighborhoods and the militarization of policing . Currently, the Pentagon provides many departments with excess equipment such as assault rifles, grenade launchers, night-vision sniper scopes, and mine-resistant, ambush-protected vehicles known as MRAPs – all at no charge.

The controversy above all focused attention on a highly visible tragedy – the frequent death of young and unarmed African Americans at the hands of white police.

|

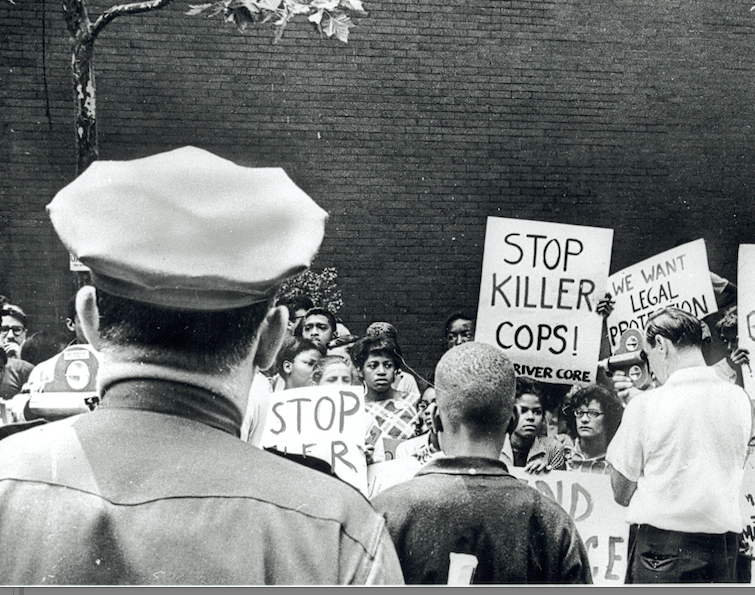

| An August 2014 "Light Brigade" stands with Michael Brown near Red Arrow Park, Milwaukee. |

But at the same time, a largely invisible calamity – invisible at least to many white Americans – has been taking place across America. By the summer of 2014 the United States had a rate of incarceration between five and ten times as high as in Western Europe and other democracies. And by a wide margin the United States had more prisoners behind bars – most of them poor young men of color – than any other country in the world.

The prison crisis at the state and federal level costs billions of dollars annually in direct spending – and this does not tally the cost of those wasted lives or the devastation it has brought on families and communities across the nation.

The historical origins of “mass incarceration” or what some have called “The New Jim Crow” are complex. But an important episode in the gradual development of America’s prison crisis came in July 1964, when Thomas Gilligan, an off-duty white lieutenant in civilian clothes, fired three shots and killed James Powell, a 15-year-old black student, across the street from a junior high school in New York City. Hours later, a black teenager with tears streaming down her face challenged and taunted a blue phalanx of white officers.

“Come on, shoot another nigger!” she cried.

In the days and weeks that followed, racial unrest spread from Harlem to Brooklyn, then to Rochester and other cities.

In the White House, Lyndon Johnson saw an immediate threat to his election hopes from conservative challenger Barry Goldwater, who had already identified “crime in the streets” as a major issue in his acceptance speech at the Republican convention. The president also saw a potential danger to his grand ambition to build a Great Society based on equal opportunity for all.

And so he took steps that would culminate in 1965 with his declaration of a War on Crime and his decision to create the Office of Law Enforcement Assistance, which significantly increased federal involvement in local policing.

Fifty years later, it is clear in retrospect that 1965 was a fateful moment for liberalism and Johnson, who simultaneously committed the United States to three wars – against crime and poverty at home and against communism in Vietnam – none of which would end well.

The wars against communism and crime even intersected when the Defense Department began to offer riot training and distribute surplus equipment to police departments, which were eager to militarize their operations in the wake of the civil unrest that erupted in the late 1960s.

In both a symbolic and real sense, then, James Powell was the first casualty in a larger conflict that has subsequently done great harm to several generations of African Americans.

The Summer of ‘64

The shooting of James Powell came at 9:20 a.m. EST on July 16, 1964, after an altercation on the steps of an apartment building across from the school.

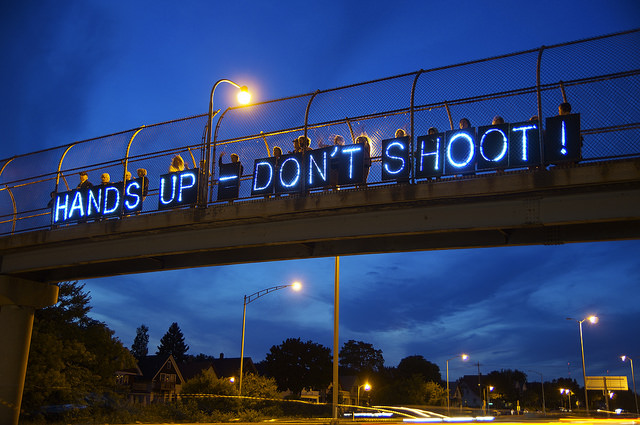

|

| During the Harlem Riots of 1964, demonstrators carry leaflets of Lieutenant Thomas Gilligan who shot and killed 15-year-old James Powell, a black student. |

At the same moment, three thousand miles away in San Francisco, aides to Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona were putting the finishing touches on his acceptance speech to the Republican National Convention. The night before, at the Cow Palace, he had received the greatest prize of his political career – the presidential nomination. Now he would announce to the American people that the conservative moment in national politics had arrived.

At 8:20 p.m. PCT, fourteen hours after Powell had bled to death on the sidewalk, Goldwater strode to the podium as the band played “the Battle Hymn of the Republic” and red, white, and blue balloons fell from the rafters. Grim and stern, with black-rimmed glasses that accentuated his angry image, he denounced rising crime and “violence in our streets” as he addressed the delegates, who responded with roars of approval.

“Security from domestic violence, no less than from foreign aggression, is the most elementary and fundamental purpose of any government,” Goldwater intoned as the crowd erupted, “and a government that cannot fulfill that purpose is one that cannot long command the loyalty of its citizens.”

The Goldwater speech in San Francisco reflected and strengthened white resistance to black demands for racial equality. It also catapulted an issue known as law and order from the margins to the mainstream of presidential politics.

|

| Portrait of Barry Goldwater |

With violent crime a daily reality in most cities, conservatives across the country, building on decades of opposition to civil rights and allegations of black criminality, hastened to blame racial integration for unleashing urban conflict.

In New York, the violence and disorder were acute.

On the streets and in the subways, muggings, murders, robberies, and rapes were rising sharply and posed a classic case of cognitive dissonance for many white liberals. Intellectually, they knew that most blacks were not muggers; emotionally, they could not ignore the sense that most muggers seemed black.

Adding to the racial tension were a disturbing number of high-profile black-on-white crimes, such as the brutal stabbing, rape, and murder of Catherine “Kitty” Genovese in March 1964 by Winston Moseley, who later confessed to killing two other women and committing at least 30 burglaries.

By summer the city was on edge.

Mayor Robert Wagner Jr., Police Commissioner Michael Murphy, and civil rights leaders publicly tried to reassure the public, but privately police officers were skeptical. “I hope this doesn’t happen,” said one veteran detective, “but more Americans may get killed in Harlem this summer than in Vietnam.”

On July 16, the same day that Powell was shot and Goldwater spoke to the nation, the National Review magazine reminded readers that over Memorial Day weekend, twenty black teens had vandalized an entire subway car, punching, kicking, and knifing the terrified passengers. It was not simply another incident of urban mayhem according to the conservative journal. “What is happening,” it commented, “or is about to happen – let us face it – is race war.”

Catherine Genovese's (left) murder by Winston Moseley (right) occurred in a borough of Queens, NY in 1964.

For blacks in Harlem tensions were also high.

Part of the reason for that was precisely the rising crime rate. African Americans were disproportionately represented among both the perpetrators and victims – and police neglect was a common complaint. Neither the NYPD, which had few black officers, nor the mainstream media, which had few black reporters, paid a great deal of attention to black-on-black crime, even when the murder rate was six times higher than that among whites.

Police corruption and brutality were also rampant according to many residents. “[T]he only way to police a ghetto is to be oppressive,” wrote author James Baldwin, who described white officers as occupying soldiers. “Their very presence is an insult, and it would be, even if they spent their entire day feeding gumdrops to children. They represent the force of the white world, and that world’s criminal profit and ease, to keep the black man corralled up here, in his place.”

Social conditions added to Harlem’s frustration and isolation. Poor housing and poor schools were major issues. Discrimination and the decline of the industrial economy denied African Americans good jobs, which led to family incomes substantially below those of whites. Life expectancy was low and infant mortality was high compared to whites. Drugs were a growing problem and even the streets were, literally, less safe – in Harlem, a child was far more likely to get killed by a car than in other neighborhoods.

Twice before – in 1935 during the Great Depression and in 1943 during World War II – Harlem had exploded and many predicted it would again soon. The only question was when.

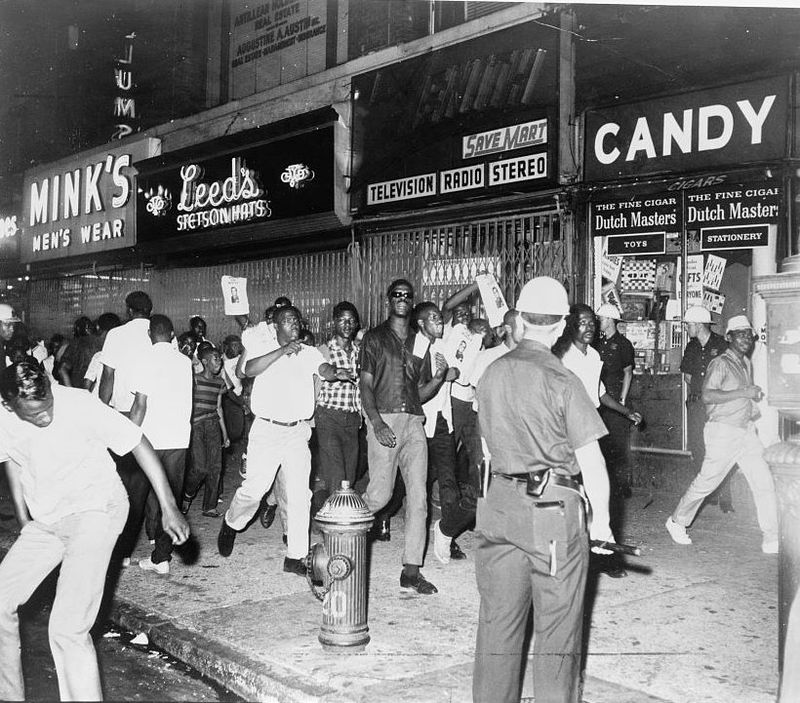

|

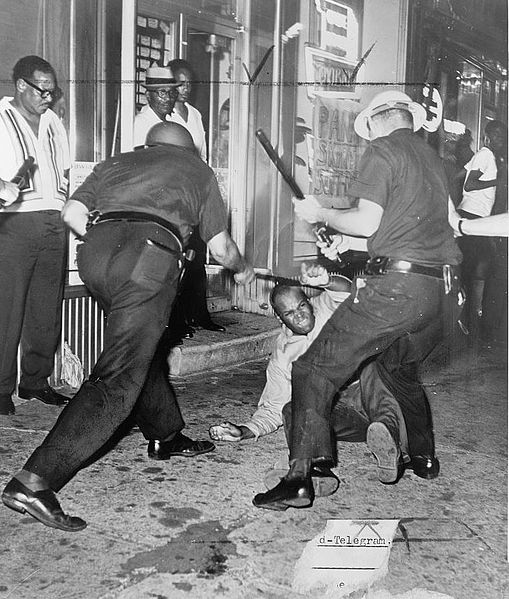

| Police confront a demonstrator during the Harlem Riots of 1964, photographed by a reporter at New York World Telegraph & Sun. |

On July 18, two days after Powell died, a planned civil rights demonstration led to an impromptu march on a Harlem stationhouse and released the floodgates of racial hostility.

For the next six nights, protests and violence rocked Upper Manhattan and Bedford-Stuyvesant in central Brooklyn as thousands of rioters looted stores and pelted police with bottles and rocks.

Although the vast majority of black residents never took to the streets or resorted to violence, by the end one person was dead, several hundred were wounded, and even more were arrested. Hundreds of businesses, especially white-owned stores, were ransacked. Many closed their doors for good, their owners financially and emotionally broken.

The police responded with live bullets – thousands of them – intended to contain the crowds and curtail the shower of projectiles from rooftops. “I saw a blood bath. I saw with my own eyes violence, a bloody orgy of police [assaults],” charged James Farmer of the Congress on Racial Equality. “This was a war – a war between the citizens of Harlem and the police.”

But Farmer and other moderate civil rights leaders were unable to restore calm, revealing a deep and widening division within the black community.

When civil rights activist Bayard Rustin, who had organized the March on Washington in August 1963 and a school boycott in New York in January 1964 to protest segregation, pleaded for peace, he was called an Uncle Tom. An angry crowd showered him with boos and chanted instead for Malcolm X, who was in Egypt. “I’m prepared to be a Tom if it’s the only way I can save women and children from being shot down in the street,” Rustin pleaded, “and if you’re not willing to do the same, you’re fools.”

In the symbolic and historic heart of black America, the Harlem Riot of 1964, as most called it, highlighted a new dynamic in the racial politics of the nation. The following weekend, the rebellion or uprising, as some described it, spread to Rochester and marked the start of the first “long hot summer” of the 1960s.

The White House and the War on Crime, March 1965

As the race for the White House reached a climax in the fall, the conservative appeal of law and order posed a mounting threat to the political dreams of Lyndon Johnson, who feared the impact of the riots. “One of my political analysts tells me that every time one occurs, it costs me 90,000 votes,” he told an aide.

|

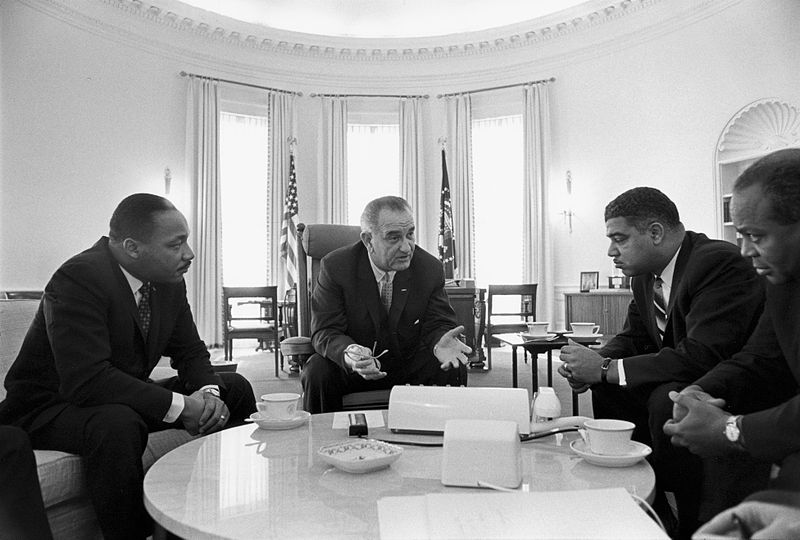

| Photograph of President Lyndon B. Johnson in the Oval Office. |

Of course, Johnson hardly needed an expert to explain it to him: As he recognized from the outset, law and order was inextricable from race. On the campaign trail, Goldwater blamed the racial unrest on black leaders like Rustin and Farmer. They and their liberal allies, the candidate claimed, had weakened respect for legitimate authority and encouraged urban lawlessness by promoting civil disobedience.

In response, Johnson recast his ambitious War on Poverty as “a war against crime and a war against disorder.” It reflected the liberal view of what caused crime and it helped him blunt Goldwater’s charge. Ultimately, the president easily won election in his own right.

But behind the scenes he and his advisers were nervous about the conservative threat that law and order – and future unrest – posed to his right flank and legislative plans. As an official in the Justice Department noted, it was fine to argue that social programs would attack the root causes of racial violence – deprivation and despair, which discrimination had exacerbated – but “the President must place a much greater emphasis on crime and law enforcement if he is to strike the right note with Congress and the public.”

In January 1965, Johnson took the advice to heart. “Every citizen has the right to feel secure in his home and on the streets of his community,” he said in his State of the Union Message. Pledging federal assistance to local police departments, he also promised to convene a presidential commission to study the crime problem and propose new solutions.

Even liberals were impressed. “Violence in the streets has become so much a part of the American way of life that most of our citizens are personally alarmed,” noted The Nation magazine, which estimated the cost of crime at $27 billion a year and argued that the White House should therefore commit far more than $1 billion a year to the War on Poverty.

In March 1965, Johnson reacted to public alarm by essentially declaring a War on Crime in a Special Message on Law Enforcement to Congress. “No right is more elemental to our society than the right to personal security and no right needs more urgent protection,” he stated in language reminiscent of Goldwater. “Crime will not wait while we pull it up by the roots,” Johnson added. “We must arrest and reverse the trend toward lawlessness.”

Among the major initiatives he announced were a presidential commission and federal legislation to create an Office of Law Enforcement Administration, which would provide small grants to local and state police for experimental programs, research projects, specialized training, and modern equipment – all in the name of enhancing police professionalism.

Reaction to the address was, predictably, mixed.

|

| President Lyndon B. Johnson meets with Civil Rights Leaders Martin Luther King Jr., Whitney Young, and James Farmer in the Oval Office, 1964. |

Some liberals took Johnson to task for raising what they considered a false threat perpetrated by self-interested law-enforcement officials. Some conservatives saw the speech as a deliberate effort to steal one of their more popular issues.

A political cartoon showed the president behind a desk with two policy papers: “Aggressive Policy in Vietnam” and “War on Crime.” Under the heading “Any More Good Ideas in There?” an aide rummaged in a file cabinet labeled “Goldwater Campaign Speeches.”

But the Office of Law Enforcement Assistance (OLEA) – the slight change in title reflected traditional concerns about federal intervention in local matters – passed without opposition. It sailed through the House by a vote of 320-0; it cleared the Senate by voice vote.

A rare consensus had formed between conservatives and liberals, aided by public fear of rising crime and the new program’s modest scope. But the OLEA marked a significant expansion of the federal role in crime control and served as a model for the larger and more ambitious Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (LEAA), which Congress created in 1968.

|

| A soldier stands observing the aftermath of a race riot in Washington D.C., 1968, following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. |

At the signing ceremony for the OLEA in September 1965, Johnson echoed the uncompromising tone John Kennedy had employed in his inaugural address. “I will not be satisfied,” the president declared, “until every woman and child in this Nation can walk any street, enjoy any park, drive on any highway, and live in any community at any time of the day or night without fear of being harmed.”

The rhetorical oversell was vintage Johnson – ambitious and risky. By hailing the neighborhood cop as “the frontline soldier in our war against crime” and promising unconditional victory – but committing only limited resources – the president had staked his political credibility on a domestic quagmire that, like the war in Vietnam, would eventually lead to attrition and stalemate.

At the moment few were critical. But by the end of 1965, the growing danger was apparent to top officials like Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach, who warned Johnson that he had to lower public expectations or face the political consequences. “It proved to be a dreadful mistake,” he recalled later. “You are meant to win wars, and the War on Crime was in a sense an unwinnable war.”

The War that Never Ends?

Katzenbach was proven right. During the next three years violent crime escalated, major riots flared in almost every large city, and student protests erupted on many college campuses. Conservatives successfully conflated these disparate phenomena, leaving liberals at the mercy of the politics of law and order.

In desperation, Johnson created the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (LEAA), which funneled federal dollars in large quantities to state and local police departments. It was part of the Safe Streets Act of 1968, which the president considered the worst bill he had signed in office, but he saw little choice.

|

| President Lyndon B. Johnson meets with Richard Nixon before his Presidential nomination in July, 1968. |

Johnson’s action made little difference. By Election Day law and order was the most important domestic issue in the nation and conservative Republican Richard Nixon rode it into the White House, pledging that the “first civil right of all Americans is to be free from domestic violence.”

Three years later, facing re-election amid rising rates of violent crime, Nixon stated that drug abuse was “public enemy number one” and declared a War on Drugs in 1971. Although the hippie user and criminal addict now joined the black mugger or rioter as potent symbols of social disorder, the first measure imposed was urine testing on Vietnam veterans returning from Southeast Asia. The War on Crime had transformed into the War on Drugs.

In New York, Governor Nelson Rockefeller, a moderate Republican, harbored presidential ambitions. Determined to bolster his law-and-order credentials and motivated by the violent uprising at Attica Prison, he signed legislation in 1973 that imposed steep minimum sentences for the possession and sale of heroin and cocaine.

Soon other states followed suit. The new laws swelled prison populations – most inmates are in state, not federal, facilities – and created a demand for ever-larger police forces.

By the mid-1970s conservative reservations about Johnson’s War on Crime had vanished. The political benefits of taking a “tough on crime” stance were clear and few objected to the federal government’s intervention in state and local affairs, perhaps because the bulk of LEAA funds were distributed as block grants to police departments in Republican suburbs, where voters were most plentiful, rather than to Democratic cities, where crime was most prevalent.

Radicals, however, voiced numerous criticisms of the LEAA.

For one, they argued that it had militarized policing by importing from Vietnam technologies and tactics like armored personnel carriers and urban SWAT teams. For another, radicals contended that promoting the concept of police professionalism reinforced the belief in police infallibility and eroded the credibility of police critics. Finally, they asserted that the LEAA was constructing a national police force with mass surveillance capabilities and stimulating a prison-industrial complex eager to pursue profits from privatization.

Outside academia the radical critique made little headway.

|

| Ronald Reagan escalated the War on Drugs during his presidency. First Lady Nancy Reagan (above) headed one of the War on Drugs newly established "Just Say No" advertising campaigns. |

In the 1980s, President Ronald Reagan escalated the War on Drugs, which he contended was vital to national security. The White House militarized interdiction programs aimed at reducing the supply of marijuana and cocaine from Central America and promoted “zero tolerance” for narcotics users through the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986.

The Reagan administration also supported the Sentencing Reform Act of 1984, which was enacted with bipartisan support from Republican conservatives like Utah Senator Orrin Hatch, who wanted less judicial leniency, and Democratic liberals like Massachusetts Senator Ted Kennedy, who wanted more racial fairness.

The legislation eliminated indeterminate sentencing for federal crimes and instituted a comprehensive grid of mandatory minimums. Within five years the average time served in federal prisons had doubled and the percentage of offenders who received probation instead of prison had fallen by half.

Despite Reagan’s focus on interdiction and incarceration, public anxiety over a supposed “crack crisis” grew in the 1980s.

To demonstrate that he was a “New Democrat” who was not soft on crime, President Bill Clinton warned that "gangs and drugs have taken over our streets" and– sounding like Goldwater, Johnson, and Nixon before him – stated that “the first duty of any government is to keep its citizens safe.”

Accordingly, Clinton signed the largest law enforcement bill in history in 1994. It expanded the number of federal crimes eligible for the death penalty and pumped billions of dollars to the states to hire 100,000 more police officers and build more prisons.

Declining Crime, Police, and Prisons Today

By the first decade of the 21 st century, the social, economic, and political impact of the War on Drugs and “mass incarceration” was evident. As the Defense Department distributed surplus equipment from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan under the 1033 program, aggressive policing expanded the widespread criminalization of urban spaces and devastated minority neighborhoods.

Although the growth of public prisons brought some jobs and revenue to rural, usually white, communities, the proliferation of private prisons, as the radicals had predicted, generated sizable corporate profits. At the same time, the drive to create “factories with fences” and exploit prison labor eroded wage levels and weakened trade unions in certain industries.

Widespread felon disenfranchisement laws also stripped a basic right of citizenship from both prisoners and those who had already served their time, with important implications for liberals and conservatives. In the 2000 presidential election, for example, almost two million black men could not cast ballots – including more than a hundred thousand in Florida, where Republican George W. Bush defeated Democrat Al Gore by a narrow margin.

|

| Undated photograph of teenager, Trayvon Martin. |

Twelve years later, an unarmed black teenager named Trayvon Martin was shot and killed in Florida by George Zimmerman, a neighborhood watch volunteer who believed he was in danger and cited the state’s stand-your-ground law in his successful defense. Once again, the state was not unique – more than twenty others had similar laws, which in a sense represented the privatization of policing by individual citizens.

Yet even as advocates of stand-your-ground laws stressed their necessity, violent crime was on the decline – as it had been for twenty years. New York City, for example, had 1,444 homicides in 1970, 2,228 in 1980, and 2,605 in 1990. But in 2000, it had only 952 murders and by 2014 the figure had dropped to an astounding 328.

Why crime has declined so dramatically and consistently since the 1990s is a matter of debate among criminologists and policymakers. But it has led many Democrats and Republicans to reconsider their earlier commitment to a costly regime of prison expansion and mass incarceration.

“The judicial system has been a critical element in keeping violent criminals off the street,” said Democratic Senator Richard Durbin of Illinois recently. “But now we’re stepping back, and I think it’s about time, to ask whether the dramatic increase in incarceration was warranted.” Other senators, including Republicans Mike Lee of Utah and Rand Paul of Kentucky, have joined him in supporting reduced federal drug sentences.

In 2015, fifty years after Lyndon Johnson originally announced a War on Crime, a new consensus may have started to emerge. Perhaps the U.S. will now do what some urged during the Vietnam War – declare victory and pursue other priorities.

History suggests that it will prove difficult, given the partisan polarization of American politics and the risks of appearing soft on crime.

But rethinking the strategies behind the War on Drugs, altering the perceptions reinforced by it, and redeploying the resources committed to it might help prevent another generation of black men from spending their lives behind bars or losing their lives on the street like Michael Brown, James Powell, and Trayvon Martin.